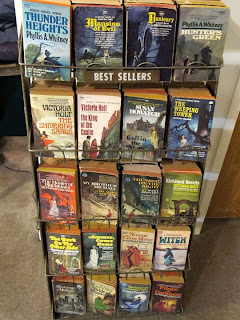

Part of my collection of vintage Gothic Romance paperbacks displayed in a vintage paperback book rack.

Tuesday, November 29, 2011

Wednesday, November 23, 2011

An Appreciation of Barbara Michaels Part I: Ammie, Come Home

After finishing my first novel (a lurid, over-the-top occult potboiler) I decided I wanted to try my hand at a more traditional Gothic romance, so I spent a few months rereading a number of old paperbacks from my collection. Of course, I had to start with Barbara Michaels. I had reread her first two books, Master of Black Tower and Sons of the Wolf, about a year before, so I picked up Ammie, Come Home, and was reminded once again what an underrated gem of a ghost story this little book is.

First published in 1968, a full two years before William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist made this type of old fashioned ghost story all but obsolete, Michaels’ tale of avenging ghosts and spiritual possession pushed the envelope for the Gothic romances of the era. The bona fide supernatural was not a popular theme among Gothic romance purists, and despite her continued popularity forty-odd years later (Michaels’ back catalog has never gone out of print), readers of old school Gothics still have difficulty embracing Michaels as the premier American Gothic novelist of her day. Ammie, Come Home was to be the first in Michaels’ unofficial occult trilogy.

Beginning with Ammie, Come Home and continuing throughout the rest of her career under the name Barbara Michaels (she is better known as Elizabeth Peters of the best-selling Amelia Peabody mystery series), Michaels makes a concentrated effort to subvert and expand the conventions of the Gothic romance genre which was enjoying it’s heyday in the late 60s and early 70s. Here, the protagonist is a middle aged, widowed aunt, and the romantic lead an irascible red-headed anthropology professor in his early fifties, but the romance takes a back seat to the ghostly manifestations.

Our heroine, forty-something Ruth Bennett, takes a casual romantic interest in her niece Sara’s anthropology professor, Pat McDougal, and soon Ruth has scheduled a séance in her historic Georgetown home after meeting a famous society medium at a fancy soiree. First mistake. Before you know it, niece Sara is speaking in an otherworldly voice and violently attacking her aunt with no recollection of her actions in the morning. Said anthropology professor plays the devil’s advocate throughout, eager to cart Sara off to an asylum to have her checked out for multiple personality disorder. But Sara’s boyfriend, Bruce, and Aunt (and of course, we readers) know better. It seems Ruth’s home was the scene of a Civil War era domestic drama, and not only Sara, but Bruce, Pat, and Ruth are all players in the necessary reenactment of the crime and its vengeance.

No one will ever mistake Barbara Michaels’ books for being high brow Gothic literature of the Shirley Jackson variety, but Michaels has clearly done her research, managing to tell a rollicking tale of the supernatural judiciously sprinkled with arguments, both pro and con, to support the theory of ghosts and possession.

Whether you have or have not experienced Ammie, Come Home for yourself, late autumn is prime time to snuggle up on the couch with a classic late 60s ghost story while the November winds rattle the windows and icy tendrils snake their way across the floor. And if you listen carefully, you just might hear a voice calling to Ammie in the lonely darkness outside your window. ”Ammie…come home!”

Harry Bennett cover for the 1969 Fawcett Crest paperback edition

Thursday, November 17, 2011

Dzaet - The Art of Pamela Hill

A crescent moon ascends a benighted sky. A woman’s hair becomes a tangle of leafless, lifeless tree limbs. A Victorian woman navigates the forest of souls, pestered by a flock of ravens with human faces. A wide-eyed beauty strikes a formal pose, the severed head of Edgar Allan Poe in her lap.

Enter, if you will, the World of Dzaet, the Art of Pamela Hill.

One of the joys of internet social networking sites is the discovery at the click of a mouse, of something, or someone, new and wondrous. This is how I discovered Pamela Hill in the autumn of 2009 and purchased for my own, a print of the painting, Annabelle Lee.

Besides her uncanny ability to conjure deeply personal visions from the depths of her soul that resonate with people who have never met her, one of the most startling facts about Pamela is that she is completely self taught, having picked up the brush as recently as 2007, and has already made a name for herself throughout her home state of Virginia and as far away as the European continent.

Pamela, can you tell me a little bit about how you got your start. What made you decided to take up painting at mid-life, and how did you go about developing your techniques?

Well, Barrymore, in all honesty, I am not sure how I got my start. I was bored one day, and simply decided to try my hand at a painting. I had always been interested, had "dabbled" in art in my teens, but never pursued it. It was hilarious. However it was also addicting. By the third painting, I found that all of my childhood angst was being poured out on canvas. The paint was mixed with tears, and although it was emotionally taxing, something deep inside me knew that it was a path that I had to walk down. So, I walked. It was exciting, yet difficult. It opened wounds, and it healed. Those early canvases were rudimentary, yet filled with stories of my life. I never worried about technique during that time. I just wanted to empty myself of all the bottled up pain, and so I continued.

From past conversations with you, I understand how difficult it is for you to part with your original paintings, even though in less than five years you have developed a hobby into a full-time professional career. How did you come to publicly display your first painting, and how did you feel when you made that first sale?

Yes, it is extremely difficult for me to part with my paintings. For obvious reasons, I keep a canvas journal. Each and every one of my paintings are autobiographical, so when one of them finds a new home, a part of me leaves with it. Sometimes as humans it is difficult for us to give up the past, to let go of anger. At times I wanted the paintings around to remind me of how justified I was to have those negative emotions. When I do let a painting go, it is the ultimate in healing for me. I have finally reached the place where I am willing to let go of that past and forgive.

I don’t consider what I do a career, it is more of a service. Each painting touches the person that it is supposed to. The client resonates with it personally, and perhaps it begins their own road to healing. I found this when a close friend of mine "talked" me into posting a piece on MySpace, and the piece was received with messages from people who had been through the same emotional upheaval. That encouraged me to take the advice of a friend at a local art shop who had wanted me to try a show. At the first show, I found myself holding a young woman who cried her eyes out. I gave her the painting, as I realized that she needed it to begin her own path. I finally had found a reason for the suffering I had endured.

Are there any particular artists who influenced your particular style and/or any artists that you admire and strive to emulate?

I have no art history knowledge at all. I am not well acquainted with other artists, so there was no one in the beginning that influenced me. I will say though, that one woman eventually did touch me. I was in Barnes and Noble looking through their clearance table when I saw a book about Frida Kahlo. I opened the book, looked at a few of her paintings, and thought “WOW this woman paints like I do!” I had no knowledge of who she was, or that she was no longer alive. I bought the book, then the movie, and learned a lot about her. Although our styles are not necessarily the same, she was also a symbolist, and she painted her life on canvas. I have since completely resonated with her as a human being.

As I life long lover of all things Gothic, from art to film to literature, I often find myself asking: Why Gothic? Where did this inclination toward the dark exploration of the soul come from? What do you think has influenced your life and art to lean toward the types of dark and atmospheric images that appear in your work?

Yes, Barrymore, I love all things Gothic. However, I don’t purposely paint in any style. I simply use my symbols to tell a story, and my stories are dark and painful. Again, they are autobiographical. As a writer, imagine getting up every morning and writing about your personal feelings, upsets, joys, etc. That is all that I do.

Are there any particular books or films that influenced your Gothic leanings as you were growing up?

You know, I don’t really know why I love the Gothic world. My first thought would be that I love the Victorian clothing. I simply adore everything from corsets and ruffles to the beautiful architecture and furnishings. Perhaps I was alive in that era? I would guess so.

I know that many of your paintings are deeply personal. This one, Out of the Darkness and Into the Light, has been described as a self-portrait. Would you be willing to share with my readers what some of the imagery means to you?

Yes, it is a self portrait. The title gives away some of the meaning. I was lost and now am found. This particular painting was meant to show my growth in the spiritual aspect of life, thus the blue corset, which symbolizes spirituality, and the owl’s head which symbolizes the wisdom that I have gained. She is walking out of, or away from, the darkness felt from feeling alone, and into the knowledge that we are all one. All things are one, and there is never any need to feel alienated or alone. Just look around you at any given moment and know that you are surrounded by "family". She holds the light, it is no longer unattainable. She has found her place in the world, in the universe. She is content.

One last question, one I’m sure you have been asked more times than you can count, what is the meaning of Dzaet?

I love this question. The answer always reminds me of the journey that I have taken and the wondrous outcome of it. Dzaet is Armenian for the numbers 808. I was born at 8:08 in the morning, and when I picked up the paintbrush, I feel that I was re-born. Reborn into a new purpose, a new life, a new path. It seemed appropriate that I would paint under that name. After all, how much more boring could "Pam Hill" get? And for those who know me personally, I deplore boring!

One thing is certain your artwork is never boring! Thanks so much for allowing me the opportunity to share your work with my readers. Pamela’s work can be found online at Dzaet, MySpace, and on Facebook at Dzaert Art. All images included here are copyright by Dzaet, reproduced with permission.

Friday, November 11, 2011

Charles Geer, American Illustrator

Charles Geer (1922 – 2008) was an American illustrator and author. Best known for his illustrations in numerous children's books, including The Mad Scientists' Club published between 1960-1968, Geer was also a prolific hard cover jacket illustrator for Dodd Mead, William Morrow, and other publishers of Mysteries and Gothics throughout the 1960s.

I have always been fond of Geer's use of watercolor techniques to convey mystery and emotion in his jacket paintings, from the cool shadows on a hot summer day as in Return to Aylforth, to the splendid sunset of Black Is the Colour of My True-Love's Heart and the light reflecting on the storm tossed waves in Lyonesse Abbey.

All scans are from my personal collection. No copyright claimed or intended.

Saturday, November 5, 2011

Things Are Looking Mighty Grimm

Little Red Riding Hood leaves her college dorm room dressed in pink running shoes and a tight red sweater, iPod cranked up to “Sweet Dreams” by the Eurythmics, and sets out for an early morning jog through the forest primeval. Minutes later, amid snarls and thrashing underbrush, Little Red is torn limb from limb.

Goldilocks and her boyfriend break into a secluded house, looking like something out of a primitive Tiki bar, helping themselves to the contents of the wine bar, the fridge, and a little R and R in the homeowner’s bed. Little do they know they have stumbled into the lair of three “bears.”

If this sounds like the dark flip side of Disney, you’ve got it right. It’s NBC’s breakout new cop thriller, Grimm. Our hero, homicide detective Nick Burkhardt, recently learns that he is a “Grimm”, a descendant of the original Brothers, blessed or cursed with the ability to “see” our favorite storybook monsters for what they really are. Drawing on a long tradition of supernatural television from Rod Serling’s Night Gallery to The X Files, Grimm infuses new blood into that old standby, the TV cop show.

One of the best things about Grimm is its visual style, thanks to the producers decision to film the show in and around Portland , Oregon , where the woods possess a natural fairy-tale like quality not unlike Germany ’s Black Forest . But this is network television, so the violence is nowhere near as graphic as, say HBO’s True Blood, and the 45 minute plots are not overly complex, nor is there any envelope pushing here.

Grimm airs in the perfect time slot, early Friday evenings after the gym and happy hour, and before more serious late night partying begins. For those of us whose tastes lean toward the Gothic and Supernatural, it’s a great way to kick off the weekend.

Grimm airs Friday nights at nine on the NBC network. The first two episodes are currently available for online viewing at Hulu dot com.

Tuesday, November 1, 2011

The Pit and the Pendulum (1961)

For kids growing up in the US in the 1960s, Saturday night television was a thing of wonder when we were allowed to stay up late with a bowl of popcorn and a bottle of root beer, shivering with anticipation as the minutes kicked down to the start of our local fright show. In my city it was called Scream In and was hosted by a groovy hippie vampire named The Cool Ghoul. Week after week he brought us the best in (mostly Gothic) horror films from the 40s, 50s, and early 60s. We saw our first Hammer films on these programs, low budget shockers such as Francis Coppola’s Dementia-13, dubbed Italian imports, and of course, the Roger Corman adaptations of Edgar Allan Poe’s tales of mystery and imagination. Few things were scarier to me at that age than the bloodied hand of Barbara Steele rising from her tomb to stalk Vincent Price through the womb-like corridors of Medina Castle

British film critic David Robinson accurately pointed out, "As in (Corman’s) House of Usher, the quality of the film is its full-blooded feeling for Gothic horror - storms and lightning, moldering castles and cobwebbed torture chambers, bleeding brides trying to tear the lids from their untimely tombs." Indeed, Pit and the Pendulum is so soaked in Gothic atmosphere that I have probably watched this film on VHS and DVD more than any other. On any rainy Saturday afternoon, sleepless midnight, and of course, the Halloween season, I find myself being drawn back to Castle Medina and the ravings of Vincent Price again and again.

To today’s younger audiences who have grown up with more graphic shockers, Pit and the Pendulum might seem too cheesy to take seriously. I have to admit that if Vincent Price was any more of a ham his performance might be mistaken for Christmas dinner. But when you drill down through the blood and thunder soundtrack by Les Baxter, the lashing rains and crashing waves, Daniel Haller’s art direction which fills the frame with an almost unparalleled Gothic atmosphere (watch for more about this guy in future posts), what we have left is a truly disturbing portrait of a mind on the brink of psychological collapse.

For those not familiar with the plot of Richard Matheson’s adaptation (spoiler alert), Don Nicholas Medina (Vincent Price) is the son of Sebastian Medina, one of the Spanish Inquisitions most notorious torturers. At an early age, Nicholas witnessed the death by torture of his Mother and Uncle at the hands of his Father, accusing both of marital infidelities. Here we have what is unofficially known as Wicked Father Syndrome, a motif found in several of Corman’s horror films as well as a staple of 20th century romantic Gothic fiction. This psychological fissure casts Medina Elizabeth Elizabeth Elizabeth is dead, which brings us to the memorable scene of Elizabeth

If Pit and the Pendulum were to be adapted today, the film would undoubtedly focus on grisly torture effects, much as it did in a 1991 version. With its music, art direction, atmospherics and emotional histrionics, Corman’s 1961 film remains one of Gothic cinema’s major milestones.

“Neeeecholas!”

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)